Exploring a Theoretical Framework for How Students May Be (Inappropriately) Directed Into STEM.

Overview

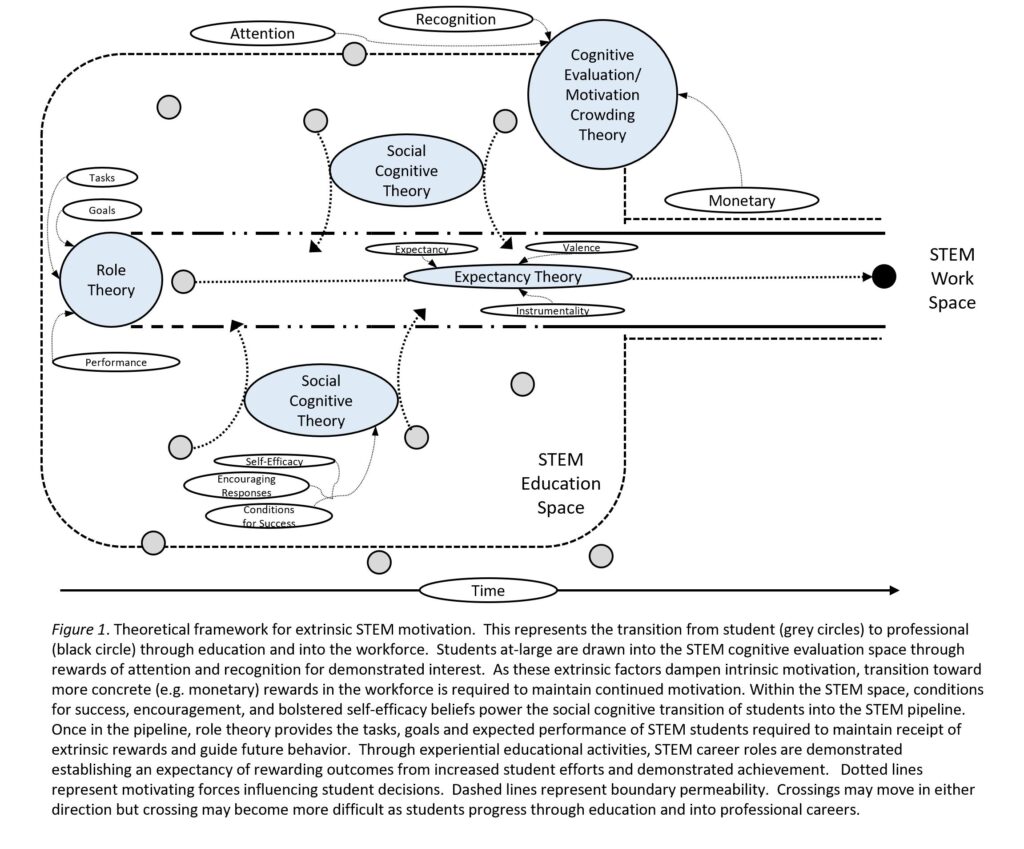

The progression of students into and through K-16 STEM programs can be described through a form of directed constructivism. Students develop or construct knowledge and understanding through their experiences in the environment, and these experiences may be more or less self-directed depending upon the sociocultural influences of that environment. Learning and development is tied to experiences in the social world and in particular, the influence of others more experienced than the learner can greatly affect the effectiveness and direction of learning (Vygotsky, 1978). The decisions students make to pursue a path in STEM education may therefore be influenced by certain elements of their sociocultural environment and those elements are represented here by the following theories. Cognitive evaluation theory describes the influence of external motivators for an activity and the corresponding decrease in internal motivation that may result from relying on outside forces to drive action (Deci & Ryan, 1985). Social cognitive theory supports social learning and observing others for use as models of desired behavior. Support, both social and physical, helps to bolster a sense of self-efficacy and produce an effective learning environment (Bandura, 2001). Role theory supports both identification of one’s place in the greater sociocultural environment and the expectations that environment places on the individual. The clarification of boundaries provides predetermined guidance for learners’ behavior and actions (Biddle, 1986). Finally, expectancy theory relates anticipated outcomes with associated actions (Vroom, 1995). Educational goals may be socially defined and linked to a particular benefit or utility, which then guides learners to pursue these goals in order to achieve the expected outcome. This framework is is designed to support investigation of the research question: How does extrinsic motivation direct students into STEM careers for which they exhibit inadequate intrinsic interest?

Cognitive Evaluation Theory

Cognitive evaluation theory describes a behavioral response where the application of extrinsic rewards or motivators to a behavior subsequently reduces the intrinsic motivation available for the same or similar behaviors due to a perceived externalization of control (Deci & Ryan, 1985). Essentially, the reason why one would perform a task has shifted from an internal desire to an external requirement, resulting in a loss of intrinsic motivation. Self-motivated practice of skills is an important aspect of learning (Piaget, 1962, p. 150). Social conscription of a student’s intrinsic interest in STEM and creation of an educational environment that perpetually recognizes and evaluates the status and development of this interest moves control of the student’s STEM related actions away from the student and into the sociocultural environment. The learner’s interest in STEM likely remains and continues to develop, but the basis for the interest is no longer centered within the learner.

Three key aspects to cognitive evaluation are: Shifting the identified drive for action away from the learner will dampen intrinsic motivation, external influences will affect a learner’s intrinsic motivation based upon the effect of the influences on perceived competence, and rewards will influence the externalization of drive, perceived competence, and intrinsic motivation according to the degree of control over or liberation of the learner they provide (Deci & Ryan, 1985). To have impact, these effects must have salience and expectancy, or meaning to the learner and reasonable likelihood of occurrence (Deci & Ryan, 1985), but may otherwise vary in form taken (Frey, 2012). In the case of STEM education, this may consist of increased attention, recognition, or rewards for exhibiting educational interest and efforts. Later this may evolve into monetary compensation for internships and other related work experience within STEM.

Social Cognitive Theory

Interaction between students within STEM education promotes learning through social experience and observation, and is described as part of social cognitive theory (Bandura, 2001). Learning is influenced by the interaction of the individual with the observable behaviors of others, the individual’s confidence in their ability to perform similar behaviors, their actual ability doing the behaviors, as well as support and encouragement from the physical and social environment. The combination of an observer’s sense of self-efficacy or perceived ability to succeed in a behavior, receipt of encouraging responses for completion of behaviors, and the conductivity of the learning environment for success influences any subsequent efforts to reproduce the observed behaviors (Bandura, 2001). In this sense, students use their peers as models of activity and behavior and progressively increase their knowledge, understanding, and engagement with STEM. In addition to peer support, educators, parents, professionals, and other STEM role models provide the encouragement, verbal persuasion, and additional mental or physical support needed to bolster student self-efficacy and increase outcome expectations. This encourages development of the requisite skills and furthers student progression into more formalized STEM education pathways.

Role Theory

Biddle (1986) describes role theory as defining the accepted and desired characteristics of established roles in society. Role theory suggests that much of a person’s activity serves primarily to fulfill their role, and that role may influence or define the behaviors a person elicits. Role theory establishes what goals to pursue, what tasks are necessary, and what performance is required. Key aspects of role theory include consensus, conformity, and role conflict. Consensus informs socially agreed upon expectations for behavior where those in a role know how they are to act and those outside know what they can expect. Conformity implies behavioral compliance, and may stem from either social imitation or deliberate emulation of role models and peers. Finally, role conflict may arise when there is a public and personal disconnect in the expected behavior associated with one’s role, leading to disruptive stresses and pressure (Biddle, 1986). Students therefore maintain proximity to their selected STEM pathway (i.e., role in STEM education) through a combination of behavioral role fulfillment (as defined by educators, career domains, etc.) and behavioral emulation of others in the same role. In the case of role conflict, disparity between expected and enacted behaviors may cause a reassessment of the student’s role in STEM education. This can push the student away from their established STEM pathway, back into the broader STEM education space where they may expand their STEM experience through resumed social interactions and potentially progress toward another formalized STEM pathway. As education advances, STEM pathways become more specialized and technically demanding. This inhibits changes into or out of a given STEM pathway by virtue of this student role becoming increasingly differentiated from alternative STEM and non-STEM roles.

Expectancy Theory

Students are expected to make forward progress along their increasingly demanding STEM pathway, fulfilling their role in STEM education. Incentive for this progress emanates from the anticipated utility of a potential outcome, socioculturally defined here as a professional position in a STEM field. This describes an aspect of Vroom’s (1995) expectancy theory, the premise of which is that while the choices a person makes may not always be the best choices, the person considers them the best for their purposes at the time they are made. Essentially, even though the outcome cannot be known a priori, actions result from decisions that appear to support the most preferred outcome. Preference here is given to the direction rather than the intensity of actions, leading students along their identified STEM pathway toward the anticipated goal. It is noteworthy that the potential utility of a particular goal may be more closely related to where the goal may lead rather than satisfaction with the goal itself (Vroom, 1995, p. 18). A professional position in STEM may therefore represent more of a means to an end than an end in itself.

There are three key aspects to expectancy theory: valence, instrumentality, and expectancy. Valence is similar to incentive, attitude, and utility and indicates a preference in potential outcomes. This is in contrast to need, motive, value, and interest which suggest an intensity of desire for potential outcomes. There may be significant discrepancy between the expected and actual satisfaction of particular outcomes (Vroom, 1995). Instrumentality represents a relationship between outcomes, or the potential that achieving one outcome will lead to another desired outcome. It may also be considered in relation to the likelihood of success of such an outcome (Van Eerde & Thierry, 1996). Expectancy is the belief that a given action will result in a particular outcome, and may also be interpreted as the likelihood of an effort yielding a result (Van Eerde & Thierry, 1996). Expectancy thus represents a relation between actions and outcomes. Together, the elements of valence, instrumentality, and expectancy define a goal and identify its potential utility to students following a STEM education pathway. As long as students can identify a goal that offers potential satisfaction and appears achievable, they have an impetus for action toward forward progress along their STEM pathway.

Combination of Theories into a Framework

The theories described above help to frame and clarify the processes that impact student decisions to enter and persist in STEM education fields. Where student engagement with STEM related activities may be initially casual and sustained through intrinsic forces, cognitive evaluation theory now isolates this engagement within an educational frame, subject to formal evaluation and judgement. Motivation shifts its locus, transitioning from personal fulfillment toward external achievement, resulting in slow diminishment of self-determination (Deci & Ryan, 1985; Frey, 2012). Within the social structure of education, social cognitive theory further draws students into STEM aligned roles. Regular interaction and supportive environments foster the acquisition and transfer of knowledge through demonstrated behaviors. Encouragement coupled with successful experiences builds self-efficacy (Bandura, 2001). Combined, these encourage commitment to a path toward STEM education, framed by role theory. Acceptance of this STEM aligned role both defines what others expect of the student and what the student expects of themselves, further dampening self-determination. Similar to the behavioral influences of social cognitive theory, role theory describes behavioral compliance through social conformity (Biddle, 1986). Overall, this stabilizes the student’s role and maintains their position along the STEM pathway. In as much as the goal of STEM education is to progress toward a professional position in STEM, progress must be made to that end. Through expectancy theory, the driving force can be explained as the student’s expectation that successful completion of their educational path (i.e., their STEM education role) will be instrumental in obtaining their preferred outcome, a professional position in a STEM field (Vroom, 1995; Van Eerde & Thierry, 1996). In combination with effects from the other theories such as shifting motivation from intrinsic toward extrinsic (cognitive evaluation theory), emulation and conformity of behavior (social cognitive and role theory), and increase of self-efficacy (social cognitive theory), this supports the actions that drive the progression and belief in the achievability of the end goal.

References

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory of mass communication. Media Psychology, 3(3), 265–299. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532785xmep0303_03

Biddle, B. J. (1986). Recent developments in role theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 12, 67–92. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.12.1.67

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York, NY: Plenum Press.

Frey, B. (2012). Crowding out and crowding in of intrinsic preferences. In E. Brousseau, T. Dedeurwaerdere, & B. Siebenhuner (Eds.), Reflexive governance for global public goods (pp. 75-83). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Ginsburg, H. P., & Opper, S. (1988). Piaget’s theory of intellectual development (3rd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Piaget, J. (1962). Play, dreams and imitation in childhood. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

Van Eerde, W., & Thierry, H. (1996). Vroom’s expectancy models and work-related criteria: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(5), 575-587. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.81.5.575

Vroom, V. H. (1995). Work and motivation. San Francisco, CA: Josey-Bass.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.